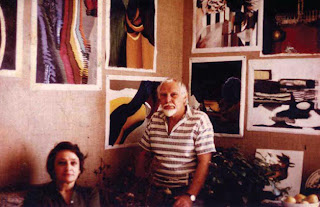

Jocelyn and Carl Plate in their Paris Studio, rue Simon le Franc, 1975

Jocelyn and Carl Plate in their Paris Studio, rue Simon le Franc, 1975Carl Plate : Within and Without 1

‘I’m trying to suggest another level which is a combination of what is seen and what is not seen, and finally to create something which exists by itself outside any visual experience. … Inside all my [work] I hope there is some little heart that people will recognise. But it is imprecise. I can’t say any more about it.’2

My father was a serious artist. Early each morning he disappeared up to his studio, built amongst the angophoras and banksias on a slope behind our small fibro house, in the hills behind the Woronora River. He reappeared to make himself a messy coffee, grinding beans in a hand grinder and pouring hot water through a paper filter. There were no coffee makers in 1950s Sydney and this ritual, along with red wine in the evenings, rewrote daily the thread of connection to a wider, cosmopolitan world. As children we weren’t allowed in the studio, to disturb the hallowed space of creation. It was a large, square wooden room, with tall windows along the northern wall and a window to the south, where his easel stood. A workbench ran under this southern window, holding shelves of painting materials, jars of vividly coloured powders and paint brushes, high stacks of Paris Match, Lilliput, Cahiers D’Art, Art International, Art News and other magazines.

On the bench stood a pot of the rubber solution glue used to stick down the collages; over time, as its gluing properties evaporated, it left behind yellowish-brown marks and disconnected pieces of paper. Rubber solution would become the bane of my life as I embarked on the process of cataloguing, repairing and preserving the collages in 2007-08.

Walls of books and more magazines surrounded a single bed behind the easel. An autodidact who’d left school at 15, he usually read three or four books at a time: Montaigne, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Balzac, Bauhaus 1919-1928, El Arte de Gaudi and the Penguin Classics. Paintings stacked thickly against the western and eastern walls.

Carl described his studio and work method to Hazel de Berg, in 1962: ‘I can only say … it has taken me a long while to get into use; I spend at least five days in there.’ [The other two days and every evening he managed his Notanda Gallery business.] ‘I don’t rush up in the morning and start painting. I may, if I’m following a line or something from the previous day, continue it, but normally I would perhaps potter round, working on some small suggestion or something that I’d seen or had in mind … like seeing a little glint of something somewhere, or imagining it, … a sort of will o’ the wisp which has no stable form, it’s a sensation, a thing that ultimately you hope will operate … in several layers of experience. This thing, as you can imagine, is extremely nebulous, but if it’s going to be seen by anyone else obviously it has to have some shape or form, to be put down somewhere. One makes a small maquette, a very small piece of note you might say, and if this appears to have some life, it is then a very faint flickering thing, one might develop it perhaps a bit more; it is a process of breathing on this tiny little flame.’3

Unless our father was working in his possum-proofed, fenced-in vegetable garden, picking beans or Warrigal spinach, we’d ring a bell to summon him down from the studio to dinner. No talking during the AB C seven o’clock news; he was not fond of Robert Menzies. There was no television but there were often guests – Godfrey Miller, Karel Kupka, Costas Taktsis, Alistair Brass, Syd and Rosalie Gascoigne, Billy and Sharn Rose, Leonard and Mona Hessing, Guy and Joy Warren, Margo and Gerald Lewers, John Olsen, Clifton Pugh, Margaret Olley, Adrian Rawlins, Reg and Janet Matthews, Francis and Charina Oeser, John and Joan Stephens; many regularly stayed for several days. Close friends, the artist, teacher and critic James Cook and his wife Ruth, built a house in the bush next door. After Cook’s sudden death, Ivan and Colleen McMeekin, potter and cellist respectively, moved in with their two daughters.

Occasionally we held wild parties. Dozens of artists, curators and friends made the long trek out through southern suburbs to our house in the bush. Many were still there the next morning, sprawled asleep on the grass when we woke early, to be sent to the corner shop for bread and eggs to feed the hangovers. It was an odd, Bohemian existence, veering from extreme isolation for both my parents, to bursts of conviviality and intense discussion, intercut with music collected by my father from all over the world: Cameroon, Paraguay, Django Reinhardt and Duke Ellington.

Carl Plate veered between movement and stasis. Although of few means, he travelled extensively. Most of his collage was produced on long sea voyages on cargo ships; in 1959 he travelled to Paris and London to exhibit at the Leicester Galleries, the first solo show by an Australian abstract artist in London4 and in 1962 he travelled to New York for a solo show at the Knapik Gallery. He produced another batch of collage on sea voyages in 1965, 1968 and 1970-71, when, an eternal Francophile, he lived in Paris for considerable periods, buying stock for the Notanda, and often living in the Cité des Arts. Carl and Jocelyn moved to Paris after the destruction of Rowe Street and the closure of the Notanda Gallery in 1974, until my father’s ill health forced their return in 1976. The name of one of his last collages, ‘Tough Stretch 1975’, refers to this time. Apart from this final return, all travel was by boat, undisturbed weeks at sea the perfect environment for his intense work; paper/scissors/glue the perfect materials for cramped cabins.

Thirty years later, when I approached Michael Rolfe, Director of Hazelhurst Regional Gallery, about the possibility of exhibiting the collection of my father’s unique, last collage, I had little idea of his long-term and prolific practice as a collage artist. With the help of Rose Peel, paper conservator at the Art Gallery of NS W, I began the long process of repairing 45 of the later collages, made up of dozens of thin strips of paper. In many cases each strip and each layer had to be reglued; in the process of repair I came to understand his unique method of working. Plate used multiple copies of any publications he could get his hands on – travel brochures, share reports, magazines – to repeat or stagger the pieces in a way that produces a dynamic effect.

This different form of collage took the artist in a new direction. Mounted and signed, they were less preparatory studies than exquisite works in their own right. Plate referred to them as ‘PMC’: Paris Multiple Collage (1974-6), or ‘AM C’, those produced on the boat Australis in 1974. They are exact and multi-layered; up to four layers are created to produce their rippling movement, not unlike work produced by the Czech poet Jirí Kolár, which he called rollage.5

While repairing this last set of jewels I had the good fortune to meet A.D.S. Donaldson, whose work on the Contemporary Art Society and early non-figurative art in Sydney drew my attention to my father’s long and unique history as a collage artist. I excavated the entire collection throughout 2007 and 2008, cataloguing, repairing, conserving and documenting what finally amounted to nearly 300 collages made between 1938 and 1976. With the exception of those too damaged to reproduce, the entire collection is represented, chronologically, in this book.

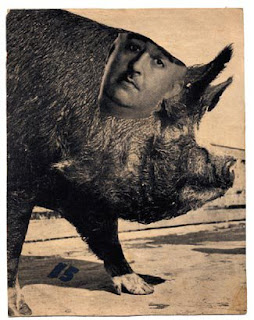

Apart from a card sent from London in 1938, and catalogue evidence of work produced and exhibited the following year, Plate’s earliest remaining set of collages were made as love poems to Jocelyn Zander, his wife-to-be, then working as an occupational therapist in Melbourne. This intimate set of playful cards often featured a pig, the subject of a joke between them. They clearly draw on his visit to the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition.6

Untitled [Franco Pig] 1945

paper collage on paper

17 x 13

Record crowds to London’s first exhibition of Surrealist art saw, among other works, collage by English artists Eileen Agar, Roland Penrose, Paul Nash, P. Norman Dawson, David Gascoyne and Humphrey Jennings. European artists Magritte, Mesens, Miro, Servais and Picasso also exhibited collage, a medium perfectly suited to the liberating playfulness of the movement. Plate described the London exhibition as ‘a turning point. I felt “this is where I come in.”’ The Surrealist exhibition ‘had the most profound influence.’ … ‘I was never part of the subconscious/Freudian manifesto, but it’s influenced the Twentieth Century; life itself is surreal. Its essential quality has always appealed. Not as a style but an attitude.’7

In 1956, six of Plate’s abstracted collage were exhibited at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Melbourne and the Macquarie Galleries in Sydney: ‘Viewed from a brief distance the collages, composed from scraps of coloured paper, might be mistaken for highly finished water colours. They are undoubtedly the best work of the kind to be shown in Melbourne in many years.’8 Of the Sydney show, Paul Haefliger wrote of the ‘number of pretty collages cut from magazines and dextrously assembled with the help of glue, one sees the artist’s struggle to wrest from his chaotic emotions a valid form, a synthesis of what he feels, observes and believes in. Here the painter stands alone.’9

Less complimentary was James Cook in the Daily Mirror, whose stated amazement about Plate’s experimentation with collages – about how any normal adult could possibly bring himself to fiddle – suggests his view of collage as ‘a form of sedative occupational therapy.’10 This must have stung; Cook was a close friend and neighbour. Carl continued making collages but never again exhibited them. In the sixties he made torn, gouged, non-figurative work, which by the seventies had developed into bold, post-futurist collages, exploring illusionistic space in a decisive shift away from earlier, more painterly abstraction.

The occasional collage has been included in exhibitions curated by Jocelyn Plate since the artist’s death. She describes collage as Carl’s way of composing, like other artists sketch; his means of transforming the world into its creative components of shape, colour and form. They reveal the exactness of his eye. ‘The finished collage never looked anything like the original thing he’d seen’ [in a magazine].11 Carl Plate’s collages are sculptural, even architectural. According to architect and writer Francis Oeser, Carl ‘had an intellectual structure within which he nurtured his interest, but it was set aside when he applied paint, or paper; when another spirit took over … a deep and un-wordy experience, a physical sense related to mystery and contradiction.’12

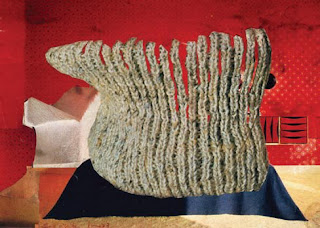

Untitled 1973

magazine paper collage on magazine paper

15.5 x 21.6

The later works defy ‘the Surrealist logic of juxtaposition of the different’ by creating a ‘multiplication of the same’.13 The repetitive pattern of narrow strips of paper creates dazzling optical effects, prefiguring certain contemporary digital work that uses time-slicing techniques, as seen in the work of Australian video artist Daniel Crooks. The late collages show an engagement with contemporary ideas of process and conceptualism.

During Plate’s fruitful collage years, 1970-76, he wrote a letter to his friend, the acclaimed Greek writer and his closest confidante, Costas Taktsis, in 1973: Art scene very depressing at the moment. Accent on youth with the latest adaptations from overseas. Happenings and ‘concepts’ played up, ‘painting’ being declared an old-hat activity. Haven’t done anything for months anyway, except prepare a mass of collage notes against the day when I feel free to do a continuous run.14

We’re grateful for that mass; they form part of the rich variety of collage work in this first book about Carl Plate.

Cassi Plate is the curator of Carl Plate: Collage

1. Within and Without is the title of a painting by Carl Plate, 1962.

2. Carl Plate, interview with Laurie Thomas, The Australian, 2/11/68.

3. Carl Plate, interview with Hazel de Berg, June 1962, National Library of Australia.

4. Adrian Rawlins, ‘Our Art Goes Over – Overseas’, Overland, No. 23, Autumn, p. 51, 1962

5. Brandon Taylor, Collage: the making of modern art, Thames and Hudson, London, 2004, p. 179-185.

6. The 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition was held at the New Burlington Galleries, London.

7. Carl Plate, interview with Richard Haese, 29 June 1974, State Library of Victoria.

8. The Age Art Critic, ‘Ingenuity Allied With Design’, Melbourne Age, 5 September 1956.

9. Paul Haefliger, Sydney Morning Herald, (late) October 1956.

10. James Cook, Daily Mirror, 1 Nov ’56. The quote is from Denise Whitehouse, unpublished PhD Thesis: ‘The CAS of NS W and the Production of

Contemporary Abstraction in Australia 1947-61’ p. 227, Monash University, 1999.

11. Jocelyn Plate, conversation with Cassi Plate, October 2008.

12. Francis Oeser, conversation with Cassi Plate, November 2008.

13. Brandon Taylor, Collage: The making of modern art, Thames & Hudson, London, 2004, p. 83.

14. Carl Plate, letter to Costas Taktsis, 16 July 1973, Carl Plate Archive.

Taken from the catalog CARL PLATE, Collage, 1938-1976

No comments:

Post a Comment